Bridges for Bighorn

Despite efforts to protect desert habitat in the southwest, major highways criss-crossing the desert are isolating wildlife into smaller pockets and hindering genetic exchange necessary to keep species healthy and resilient. Desert bighorn sheep are not exempt from this impact; they may be agile and swift, but they are no match for several lanes of speeding cars and semi-trucks, and they tend to shy away from culverts that cross under highways.

Biologists have already noticed that desert bighorn sheep populations in the Mojave and Colorado Deserts are becoming genetically isolated because the region's major highways - such as Interstate 15 and Interstate 40 - and other human developments pose a barrier to sheep movement from one range to another. According to a 2005 article in Ecology Letters, biologists found "a rapid reduction in genetic diversity (up to 15%)" among desert bighorn sheep resulting from "as few as 40 years of anthropogenic isolation. Interstate highways, canals and developed areas, where present, have apparently eliminated gene flow. These results suggest that anthropogenic barriers constitute a severe threat to the persistence of naturally fragmented populations."

Habitat Connectivity Not a Priority

This should be a familiar story, but if it doesn't ring a bell, a more widely known example can be seen in the Los Angeles basin, where the Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, and local news stations have covered the impact of highways and human development on the mountain lion population in the Santa Monica Mountains. The mountain lions there are at increased risk of inbreeding and becoming less healthy because each population is too small and largely cut off from other populations by highways that are too dangerous to cross.

If you have been following human developments in the desert then you probably know that the process for permitting new transportation, mining and energy projects often puts habitat connectivity in the back seat. Case in point, the Department of Interior approved construction of three giant solar projects and a new rail line in the Ivanpah Valley; biologists have identified Ivanpah as important to tortoise genetic connectivity. Other species at risk include the Mohave ground squirrel; this species' home range has declined as a result of urban and agricultural sprawl, and now solar and wind energy projects threaten to further fragment its habitat in the western Mojave.

For the tortoise, industrial developers that destroy intact habitat often promise mitigation money that can go toward enhancing what is left of the desert tortoise's range. However, these mitigation funds usually go toward closing illegal off-highway vehicle routes or putting up fencing along highways. This does not really address the problem of connectivity. Industrial projects that pump precious groundwater and threaten natural springs promise funds for "guzzlers" - man-made water sources for bighorn sheep. These water sources may support a pocket of bighorn sheep, but do not address the ability of sheep to move across the range and connect with other populations increasingly isolated by industrial and transportation projects.

Although the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) process will supposedly consider how to protect key wildlife corridors, the DRECP has been delayed significantly from its original timeline and it is not yet clear if the final plan will favor conservation or industry. It is also unlikely that the DRECP will properly fund wildlife overpasses for bighorn sheep without sacrificing desert habitat. The practice so far is that money for habitat improvement is provided by corporations paying to mitigate or offset the damage they are doing when they build new energy projects or housing developments. This is a vicious cycle; we need to destroy habitat in order to improve habitat somewhere else. Funding for conservation and wildlife should not depend solely on the destruction of these very treasures.

Bighorn Bridges

One measure that can be taken regardless of the DRECP may particularly benefit the desert bighorn sheep. Looking back at the mountain lion example, wildlife officials are considering building a wildlife overpass across Interstate 101 in Agoura Hills to connect two mountain lion ranges currently severed by the highway. Bighorn sheep have benefited from this approach outside of California. In Arizona, the Game and Fish Department and Department of Transportation sponsored three wildlife bridges for bighorn over U.S. Highway 93. As you can see in the video below, bighorn have been using the bridge to get across the highway safely, leading to a healthier and more resilient ecosystem.

The reason sheep need overpasses is evident in research submitted for the 2013 International Conference on Ecology and Transportation which monitored 199 bighorn sheep approaches to culverts passing under U.S. Highway 93. Only four of the sheep crossed a culvert, and the rest turned back. Sheep passed under large span bridges (probably less frightening than the narrow and low culverts), "but at significantly reduced frequencies relative to overpass utilization." Large underpasses might be more valuable for others species like desert tortoises, and could be wide enough to accommodate a natural desert substrate, such as plants to provide shade and cover for a range of different wildlife.

Research could identify the most critical choke points to determine where wildlife overpasses could best benefit the desert bighorn sheep population. One potential linkage previously mentioned on this blog could be built near the Soda Mountains and Zzyzx Road, although Bechtel wants to bulldoze desert there, instead. Perhaps another wildlife overpass could be built over Interstate 40 between Ludlow and Essex to help connect bighorn in the Mojave National Preserve to populations further south. Locations for an overpass would need to be identified based on an understanding of sheep movement habits, where populations currently exist, or where they could be restored.

We have identified a big problem - wildlife cannot move in meaningful numbers across our highways. Some wildlife cannot cross above the highway, and some culverts that cross under our highways are not suitable for all species, like bighorn sheep. We know that the problem is not going to change because our highways will not be going anywhere. If anything, our transportation corridors will only be widened as we add lanes or rail lines to accommodate more traffic. For all of the billions we invest in our roads, highways, and parking lots - with full attention paid to making sure we can fly along at 70 miles per hour, or find that perfect parking space at the grocery store - we are overdue on our obligation to repair some of the shortsighted and selfish damage we have done to the desert ecosystem. Bridges for bighorns, or more underpasses for other wildlife would be a good step.

Biologists have already noticed that desert bighorn sheep populations in the Mojave and Colorado Deserts are becoming genetically isolated because the region's major highways - such as Interstate 15 and Interstate 40 - and other human developments pose a barrier to sheep movement from one range to another. According to a 2005 article in Ecology Letters, biologists found "a rapid reduction in genetic diversity (up to 15%)" among desert bighorn sheep resulting from "as few as 40 years of anthropogenic isolation. Interstate highways, canals and developed areas, where present, have apparently eliminated gene flow. These results suggest that anthropogenic barriers constitute a severe threat to the persistence of naturally fragmented populations."

Habitat Connectivity Not a Priority

This should be a familiar story, but if it doesn't ring a bell, a more widely known example can be seen in the Los Angeles basin, where the Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, and local news stations have covered the impact of highways and human development on the mountain lion population in the Santa Monica Mountains. The mountain lions there are at increased risk of inbreeding and becoming less healthy because each population is too small and largely cut off from other populations by highways that are too dangerous to cross.

If you have been following human developments in the desert then you probably know that the process for permitting new transportation, mining and energy projects often puts habitat connectivity in the back seat. Case in point, the Department of Interior approved construction of three giant solar projects and a new rail line in the Ivanpah Valley; biologists have identified Ivanpah as important to tortoise genetic connectivity. Other species at risk include the Mohave ground squirrel; this species' home range has declined as a result of urban and agricultural sprawl, and now solar and wind energy projects threaten to further fragment its habitat in the western Mojave.

For the tortoise, industrial developers that destroy intact habitat often promise mitigation money that can go toward enhancing what is left of the desert tortoise's range. However, these mitigation funds usually go toward closing illegal off-highway vehicle routes or putting up fencing along highways. This does not really address the problem of connectivity. Industrial projects that pump precious groundwater and threaten natural springs promise funds for "guzzlers" - man-made water sources for bighorn sheep. These water sources may support a pocket of bighorn sheep, but do not address the ability of sheep to move across the range and connect with other populations increasingly isolated by industrial and transportation projects.

Although the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) process will supposedly consider how to protect key wildlife corridors, the DRECP has been delayed significantly from its original timeline and it is not yet clear if the final plan will favor conservation or industry. It is also unlikely that the DRECP will properly fund wildlife overpasses for bighorn sheep without sacrificing desert habitat. The practice so far is that money for habitat improvement is provided by corporations paying to mitigate or offset the damage they are doing when they build new energy projects or housing developments. This is a vicious cycle; we need to destroy habitat in order to improve habitat somewhere else. Funding for conservation and wildlife should not depend solely on the destruction of these very treasures.

Bighorn Bridges

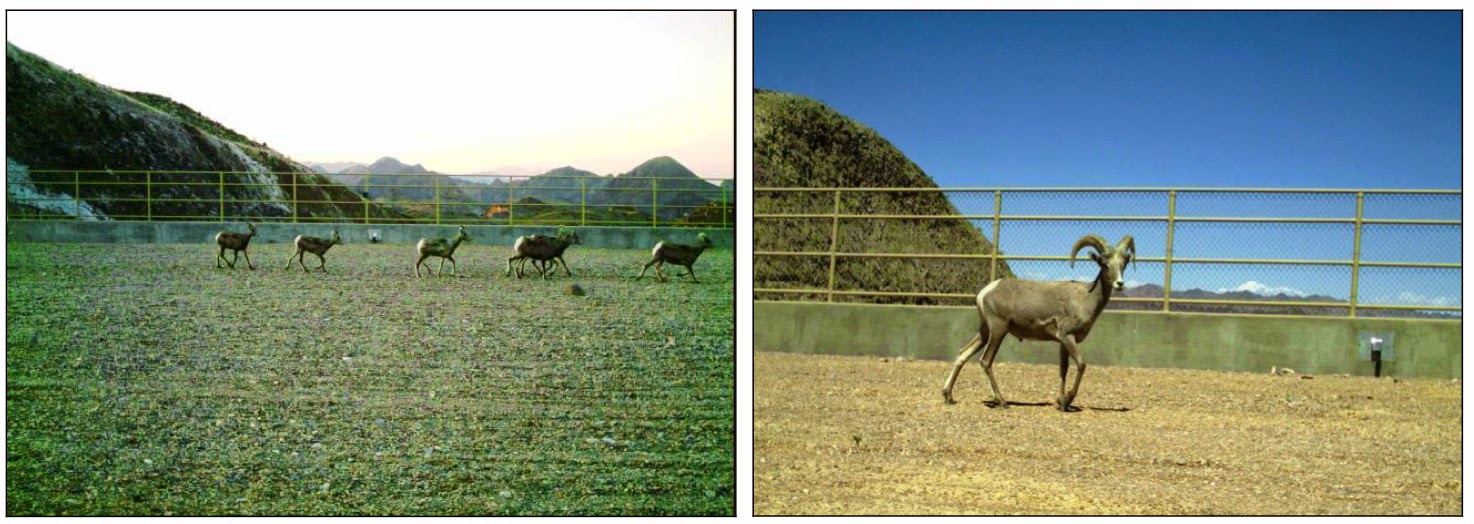

One measure that can be taken regardless of the DRECP may particularly benefit the desert bighorn sheep. Looking back at the mountain lion example, wildlife officials are considering building a wildlife overpass across Interstate 101 in Agoura Hills to connect two mountain lion ranges currently severed by the highway. Bighorn sheep have benefited from this approach outside of California. In Arizona, the Game and Fish Department and Department of Transportation sponsored three wildlife bridges for bighorn over U.S. Highway 93. As you can see in the video below, bighorn have been using the bridge to get across the highway safely, leading to a healthier and more resilient ecosystem.

The reason sheep need overpasses is evident in research submitted for the 2013 International Conference on Ecology and Transportation which monitored 199 bighorn sheep approaches to culverts passing under U.S. Highway 93. Only four of the sheep crossed a culvert, and the rest turned back. Sheep passed under large span bridges (probably less frightening than the narrow and low culverts), "but at significantly reduced frequencies relative to overpass utilization." Large underpasses might be more valuable for others species like desert tortoises, and could be wide enough to accommodate a natural desert substrate, such as plants to provide shade and cover for a range of different wildlife.

Research could identify the most critical choke points to determine where wildlife overpasses could best benefit the desert bighorn sheep population. One potential linkage previously mentioned on this blog could be built near the Soda Mountains and Zzyzx Road, although Bechtel wants to bulldoze desert there, instead. Perhaps another wildlife overpass could be built over Interstate 40 between Ludlow and Essex to help connect bighorn in the Mojave National Preserve to populations further south. Locations for an overpass would need to be identified based on an understanding of sheep movement habits, where populations currently exist, or where they could be restored.

|

| These camera-trap photos included in the Arizona Game and Fish Department evaluation shows bighorn sheep using wildlife overpasses along U.S. Highway 93. |

We have identified a big problem - wildlife cannot move in meaningful numbers across our highways. Some wildlife cannot cross above the highway, and some culverts that cross under our highways are not suitable for all species, like bighorn sheep. We know that the problem is not going to change because our highways will not be going anywhere. If anything, our transportation corridors will only be widened as we add lanes or rail lines to accommodate more traffic. For all of the billions we invest in our roads, highways, and parking lots - with full attention paid to making sure we can fly along at 70 miles per hour, or find that perfect parking space at the grocery store - we are overdue on our obligation to repair some of the shortsighted and selfish damage we have done to the desert ecosystem. Bridges for bighorns, or more underpasses for other wildlife would be a good step.

Comments

Post a Comment